Rejuvenating the Experience of “La bohème”

Jun 06, 2024

By: William Berger

La bohème became the world’s most cherished opera because of its magical ability to reinvent itself in every performance. Unfortunately, discussions around the opera tend to lack the same spirit of renewal. When we praise this work, we often fall back on the same ideas of a century ago—notions which may or may not have been true then but are clearly clichés now.

Let’s destroy them. That’s what the very believable Bohemian characters in this story would have done, and mostly because the opera is great enough to astound us without such impressions. To rehash the smartest ideas of 100 years ago doesn’t make us more intellectual, it just makes our statements antiquated and usually wrong. La bohème doesn’t need that.

You know the sentiments I’m talking about, even if this is your first time at the opera: La bohème is a “great first opera, a treasury of melody, easy to appreciate, and certain to appeal to young people because of the endearing lovebirds it depicts with immense charm (and without an overabundance of braininess to get in the way).” Most of that is plain wrong, and the rest is misleading. La bohème can be a great first opera, but only because it’s a great opera. In fact, it presents many challenges for the newcomer.

One of those challenges is the melody itself. A hundred years ago, people understood it as a composer’s signal of emotional rawness and sincerity. Today, the melody carries none of its original meaning. It sounds cheaply sentimental to audiences reeling from too much of it in bad movie scores, television commercials, and pop music played in stores to encourage consumption. I talk about opera to many different audiences of all ages, from newcomers to experts, and I never have to explain dissonance to anyone. I have to explain melody—what a composer might have been communicating by stopping the action and unleashing ravishing tones.

What still works in this opera (more than ever, in fact) is not the melody itself, but how Puccini uses it and to what purpose. This is something that has taken decades to fully appreciate. Familiarity with the score, personal and communal, is needed to reveal its shiniest veins of gold. Nineteenth-century Italian operas were designed to be heard many times—some say because it was less expensive to attend the theater than it was to heat the average home. Scores caught people’s attention with some hummable melodies, but elsewhere they provided complexities that became apparent only on repeated hearings (like Verdi’s Rigoletto).

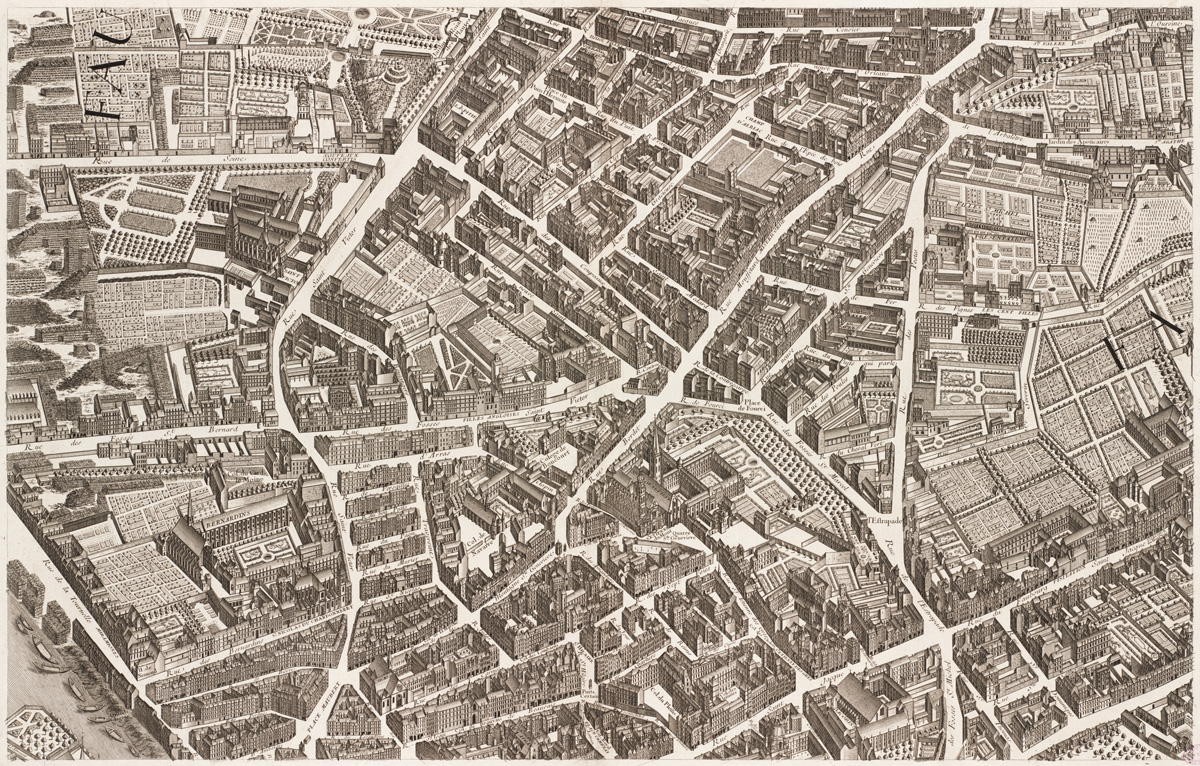

Listen to the score of La bohème—in Act I, Schaunard suggests they all celebrate Christmas Eve on the Parisian streets, and the orchestra plays a subtle planed chord theme while he rhapsodizes about the lively street scenes. That theme blares forth to open Act II, on those same streets. It then opens Act III, slower and in a minor key, as if suspended in the icy air.

It depicts something about to happen, something that happens, and then something that happened as a “frozen” memory. That’s how life seems to unfold. Behold the actual realism of La bohème. Furthermore, the complexities are impossible to hear while attending the opera for the first time. Their significance emerges in retrospect—similar to all of life’s revelations.

These characters are less genuine young people, and instead they are older individuals remembering their youth. The men here are not lower class—they’re bourgeois post-grads. No one in post-college, pre-career poverty thinks they are in their Golden Age. It only looks golden later, remembered from an office cubicle or a carpool.

The tragedy of the final scene is not so much the death of Mimi (an orchestral murmur), but instead is Rodolfo’s realization of her death, heard as thundering trombone chords. The party’s over. Hanging with and loving the other attractive, artistic cool kids won’t pay (or evade) the rent anymore. Time to move on and get a job. And that, we realize at some point, is the real tragedy. The true challenge of this opera today is that we can’t be smug or ironic about its supposed sentimentality. La bohème refers to la vie—not an individual (which would be La bohèmienne). The dead Bohemian we’ll weep for is not Mimi but rather each of us.

William Berger is an author and lecturer for a wide variety of topics within and beyond music, as well as a writer of fiction and theater works. He is a commentator for the Metropolitan Opera broadcasts and is responsible for the Met’s “Opera Quiz.”

Recommended Posts

Plan Your Perfect Visit: The Barns at Wolf Trap Guide

Sep 30, 2025 - Experience, The Barns

Backstage at Wolf Trap’s Filene Center

Jul 24, 2025 - Summer

Jamming with Jules: Music for Kids of All Ages

Jul 21, 2025 - Education, Experience, For Kids, Institute, Summer