A Turning Point For Mozart

May 16, 2018

By Roger Pines

Idomeneo was the tenth completed opera of Mozart’s career—not bad for a composer who celebrated his 25th birthday only two days before the premiere! But this opera left the previous nine in the dust. Suddenly Mozart was bringing vivid personalities to life with a wrenching emotional power he hadn’t begun to approach before.

The work was neglected during Mozart’s lifetime, and indeed, German and Austrian audiences heard it sporadically through the 19th century. A new lease on life finally came with Glyndebourne’s 1951 production. Today the rarity of performers with both the technique and the interpretive depth for the principal roles has contributed to keeping Idomeneo on the edge of, rather than entrenched in, the standard repertoire.

If Idomeneo isn’t exactly a “magic” title at the box office, one can’t blame the music. On the other hand, perhaps the dramatic content may at first glance seem unrelieved in its resolute seriousness. But look at what the piece is really about: the private agony of public personalities, communicated as powerfully as would be the case with Verdi decades later. Emotions throughout affect the listener profoundly, unlike those of so many works in the era of opera seria, of which Idomeneo is both summit and turning point.

Mozart’s opera seria predecessors took noble, historical personages and plugged them into dramatic situations focusing on love, betrayal, duty, and honor. The structure was rigid: aria, recitative, aria, with few ensembles and generally no chorus. Mozart created a hybrid: Italianate melodic flow imbuing a work in which chorus and ballet figured prominently, with recitative and aria colored by a unique fluidity. Mozart valued dramatic continuity: in any scene of ldomeneo, notice how often an aria doesn’t end formally, but moves directly into the ensuing recitative. The recitative itself may be very aria-like, moving from orchestra to keyboard accompaniment and back again, aligned perfectly to the drama.

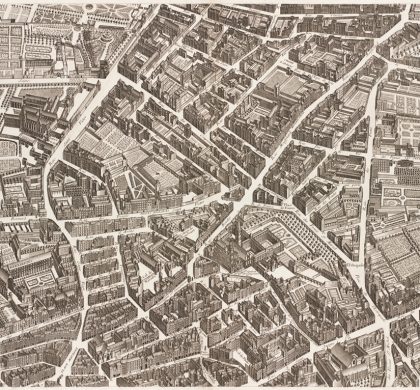

The composer longed to create a new opera, but comedy didn’t interest him at the time. He was ecstatic when the Elector of Bavaria asked for an opera to celebrate the 1781 carnival season. Mozart began work on Idomeneo in Salzburg, using a libretto by Giambattista Varesco. A Jesuit priest and poet, Varesco was chaplain for the city’s archbishop, who employed Mozart as court organist.

Varesco based his libretto on that of Antoine Danchet, written for a work premiered in Paris in 1712: Idoménée, Andre Campra’s tragédie en musique. Unlike Mozart’s version, it ends tragically: Crete’s hapless king kills his son after going insane. Danchet’s text inspired Varesco to flights of high-flown lyricism, but also to occasional stiltedness and verbosity. Mozart was not pleased: once the composer left for Munich, he communicated with Varesco using his father Leopold as intermediary.

Idomeneo premiered successfully on January 29, 1781, at Munich’s Residenztheater, and featured several singers well acquainted with Mozart. He carefully tailored the title role’s music to suit the aging voice of 66-year-old Anton Raaff. The tenor was still dexterous in florid passages, hence the magnificent showpiece “Fuor del mar.” Had Mozart not stood his ground with Raaff, we wouldn’t have the third-act quartet, Idomeneo’s musical high point; Raaff accepted that number reluctantly, having expected another flamboyant coloratura aria for himself at this moment in the drama.

Although a poor actor, Raaff could still offer Mozart polished technique and interpretive authority. He was surely unafraid to stand motionless for lengthy periods and pull expressiveness from some deep place inside himself. This is absolutely required of every principal in Idomeneo; there are no crutches, nothing to hold onto except one’s own musicality and emotions.

Mozart was frustrated with the poor vocal schooling and onstage ineptitude of castrato Vincenzo dal Prato, who portrayed ldamante, but he was lucky in his two sopranos, sisters-in-law Dorothea Wendling (Ilia) and Elisabeth Wendling (Elettra), each a highly accomplished artist. Like Pamina, Ilia grows emotionally during the opera; already in her despairing initial utterances, she’s more than a sweetly demure ingenue. Her opening scene reveals a figure in turmoil, almost Aida-like (a princess in love with her country’s enemy). Later, in “Zeffiretti lusinghieri,” the girl’s feelings for Idamante could hardly be more lovingly expressed. And finally, when Ilia proves her love by offering herself to be sacrificed, she becomes a woman, noble in her intentions and deeply touching.

Elettra is a forward-looking role, its lacerating rage and jealousy—revealed through virtuosic, wide-ranging vocalism—on a previously unimaginable scale. The Munich audience must have been stunned by the amazingly “modern” sound of Elettra’s first aria. Think of those immense leaps, alternating with passages of desperate breathlessness—what a telling aural depiction of a heart beside itself! But if this woman was to be humanized, warmth was needed, not just high-powered brilliance. Mozart provided it with the heavenly “Idol mio,” in which a softer, more feminine Elettra longs for Idamante’s love.

The fifth major character is the chorus, in this case the people of Crete. They comment on and respond to events, while also throwing the emotions of the principals into the boldest possible relief. The music demands enormous dramatic intensity and varied color, from dulcet to white-hot. Idomeneo needn’t be compared with the masterpieces that followed in Mozart’s oeuvre—it absolutely stands on its own. The work deals with matters of life and death, in which eloquence is the keynote. With that quality pervading the music, a glorious evening in the theater is assured.

Roger Pines, dramaturg and broadcast co-host/co-producer at Lyric Opera of Chicago, wrote on Rossini’s La pietra del paragone (The Touchstone) for last summer’s Wolf Trap Opera program. A frequent contributor of articles for opera-related publications and recording companies internationally, he also has appeared annually on the Metropolitan Opera broadcasts’ Opera Quiz since 2006.

Mozart

Idomeneo

The Barns at Wolf Trap

Friday, June 22 at 7:30 pm

Sunday, June 24 at 3 pm

Wednesday, June 27 at 7:30 pm

Saturday, June 30 at 3 pm

New production, sung in Italian with projected text

Running time: 3 hours including 1 intermission

Recommended Posts

You Can Go Home Again

Jul 23, 2024 - Foundation, Opera

The Ties of War & Art – “Silent Night” Director Note

Jul 23, 2024 - Foundation, Opera

Rejuvenating the Experience of “La bohème”

Jun 06, 2024 - Foundation, Opera